A Brief History of Katagami

From time to time someone asks me “How did you make this soup?” It would be easy to say that I took some bones and vegetables and put them in a pot with water, but every simple explanation pulls in more and more history. Someone, somewhere raised a chicken, not just one but generations, crafting each to yield a better chicken with each iteration. Then I bought the chicken and roasted it with some rosemary and garlic; a few days later the bones went into a pot. In its second life there is a whisper of those choices, and not just those but, all that I learned from the person who taught me to make soup.

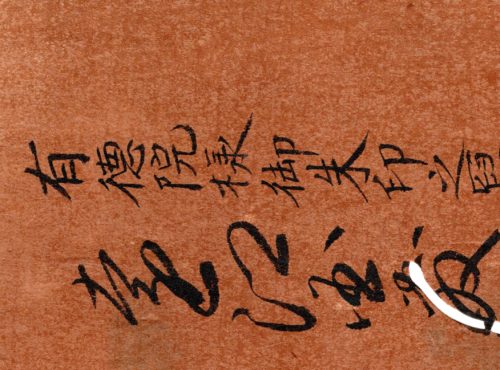

Thus it is with katagami. There is a beginning. Some say it was gilding gold patterns onto samurai armor (Kamakura Period 1185-1333). Someone cut a pattern and lay a paste through the holes. Gold leaf was placed over the leather and then pressed, embossing the design and laminating the gold onto the armor.

From there, the stories walk forward hundreds of years to a complete craft and an industry that dominated a region.

This video from the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York demonstrates this well.

Making Katagami

Starting in the Edo Period (1600-1867), the manufacture and use of katagami was so developed that single towns focused on just one element, such as making the paper for the patterns.

Making this pape takes two years. Mulberry fibre is harvested from the tree and then mashed into pulp which is turned into a paste which is then skimmed with a screen, then dried into sheets. Similar paper used for documents so those were often repurposed. That sounds easy, but even starting with washi (paper), the paper must be tanned to build strength and flexibility for use as a stencil. The paper was washed in vegetable tannin rendered from persimmons. The treated paper is cured for two years or smoked.

The stencils are made by laminating two to four sheets of mulberry bark paper with the persimmon tannin and then the design is cut using a variety of hand-made punches and knives. The pattern was drafted on the top sheet, and, often, the carver cut down a stack. Sheets were laminated together, usually in pairs, using the sticky persimmon tannin. Many designs require reinforcement so the stencil won’t tear with repeated use. Often silk threads inserted between the two carved layers (itori). This reinforcement has been fetishized; some say the thread is hair. It’s not. Most resources say it is silk. One chemical analysis identified hemp. Additional reinforcement strategies include carved tie bars, hand sewn reinforcement (itokake), and in the 20th century, laminated machine woven gause (shabari).

An Army of Skilled Workers

Each step is a process unto itself. At its height the katagami industry required an army of skilled workers to execute exact and labor-intensive tasks; pattern design, pattern printing, paper carving and silk insertion weavers. As the trade expanded, workers became specialized as they developed their trade over generations.

Salesmen traveled from town to town offering samples across Japan. Orders were taken and cloth printed. One of a thousand dyers laid a bolt of cloth along a wooden bench and pushed rice paste into the stencil openings. Once the paste dried, he dropped the cloth into a bath of indigo which turned the cotton blue in the areas that had not been pasted. He placed the cloth into a stream and the water washed away the paste. The cloth could then be sewn it into a garment.

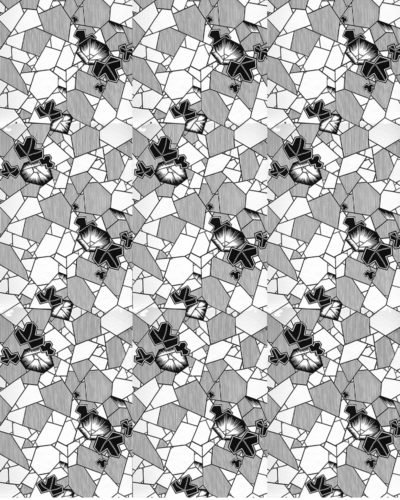

Cotton and indigo clothes were usually sewn into yukata, the casual summer kimono. There is no shoulder seam in this garment so objects in katagami patterns were placed both right-side-up and upside-down in the pattern. That way, with a koi pattern, the fish swim up and down on front and back, preventing a garment that has fish swimming up the front and down the back. That parade of fish might be exciting but would lack the elegance and balance one wants in a robe. Japanese fabrics were woven to a relatively narrow width so most repeating katagami patterns were designed to flow on the vertical. There was no care taken to ensure that the patterns lined up where one edge of fabric met another. This describes the typical use of the most common katagami stencils. There were many variations.

The stencil and its application evolved from that samurai armor until the introduction of offset lithography in 1927. By that time, artisan printing of cloth was ripe for replacing, since World War 1 (1914-18) unsettled the village populations that made up this industry. Those returning from war did not, in many cases, return to their same villages and work, which the general use of Ise katagami.

In Japan, surviving katagami document the history of surface design over centuries. The stencils themselves are seen as magnificent craft objects, documents and works of art. Presented in international expositions in the mid 19th Century, katagami and other Japanese artifacts generated curiosity and enthusiasm that inspired. They called it “Japonism.” Trade in Japanese crafts like katagami, along with porcelain, silk, and block prints, led to substantial collections of katagami in U.S. and European museums. Often these collections were centered in towns with associated industry; porcelain in Dresden, textile in London, design in Vienna and shipping ports like Salem and Boston MA hold the strongest collections. Western museums have a conflicted relationship with katagami that scatters stencils across departments described as art on paper or textile, industrial design and craft.

References & Resources

The following is a menu of resources for understanding the history, art and contemporary presentation of katagami, which I hope gives the interested user an entry point to the field.

Start Here

A great place to begin is Carved Paper: the Art of Japanese Stencil by Susanna Campbell Kuo, published by the Santa Barbara Museum of Art as the catalog to the museum’s 1998 exhibit of the same title. Essays cover the social context of textile design, the stencil and dying industry, and aesthetic and design relationships between Japan and the West. The essays are focused articles yet provide a primer on the art, craft and history of katagami. Carved Paper is my primary reference for information about katagami.

Collections

Austrian Museum of Art and Industry — Vienna, Austria.

Cooper Hewitt Museum, Smithsonian Design Museum — New York City, NY.

500+ artifacts with a curator actively presenting exhibits and online pop-ups.

Ise Katagami Kimono Museum — Tokyo, Japan.

Museum of Domestic Design, Middlesex University — London, UK.

Museum of Fine Arts Boston — Boston, MA.

Nelson Atkins Museum — Kansas City, MO.

Peabody Essex Museum — Salem, MA

Portland Art Museum — Portland, OR

Santa Barbara Museum of Art — Santa Barbara, CA.

SBMA has a small (64 objects according to their website) collection of katagami but has done more than many other institution by originating a defining exhibition and comprehensive text, “Carved Paper: The Art of the Japanese Stencil,” 1998.

Seattle Art Museum — Seattle, WA

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen — Dresden, Germany.

Victoria and Albert Museum — London, UK.

Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, Middlesex University—London, UK

Important Exhibitions and Some Projects

“Katagami Style – Paper Stencils and Japonisme.” National Museum of Modern Art, 2012— Kyoto, Japan.

“Logical Rain. Proposition II.“ Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, 2014 — Dresden, Germany.

“Cherry Blossom & Edelweiss: The Import of the Exotic.“ Textilmuseum, 2014 — St. Gallen, Switzerland.

MFA Boston x Uniqlo: T-Shirt Collection.

Contemporary Japanese clothing retailer Uniqlo, is collaborating with the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in using the museum’s katagami collection as inspiration for new clothing designs.

“Katagami: The Japanese Stencil.” Allentown Art Museum, 2019 — Allentown, PA.

“Katagami in Practice.” Museum of Domestic Design, 2016, Middlesex University — London, UK.

Symposia & Reports

These academic symposia and scholarly reports provide a map to hidden katagami collections in Europe and their influence on western design.

“International Symposium: Katagami in the West.” University of Zurich, 2016 — Zurich, Switzerland.

Google Arts & Culture: Ise Katagami Stencils. Art Research Center, Ritsumeikan University in collaboration with Kyoto Women’s University.