The Collection

The story goes like this…

My father, John Huston, (no, not the director, just an enterprising guy from Iowa) was in Europe on a project in the 1950s and 60s. He was working with an anti-looting N.G.O. which took him to auction houses, flea markets and galleries to see what artifacts were slipping past preservationists’ oversight.

He found katagami.

How’d they get there?

I doubt he was expecting antique Japanese anything when he scoured Paris’s March de Puces in 1958. But there they were, mysterious piles of tabbacco colored pages. When drawn out, they showed intricate lines and patterns carved and woven.

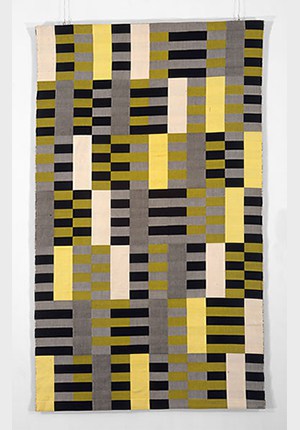

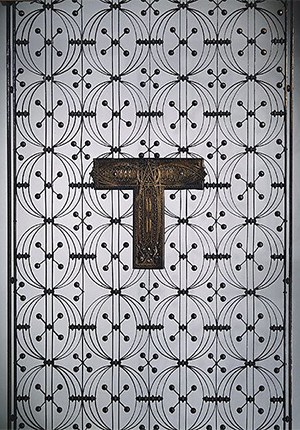

Japan opened trade in 1868. Katagami — antique Japanese textile stencils — showed up in Europe as a bit of a toss away, like the famous block print wrapped around a tea cup for van Gogh to unwrap. What was a used tool in Japan quickly became a foundation of Western decorative arts. Like porcelain and block prints, thousands of these artifacts were sold into European and U.S. collections, informing Western art and design right up to Modernism.

The years between 1890 and 1910 overflowed with graphic, decorative, industrial and fine art innovation informed by katagami: Art Nouveau, Vienna Succession, American Arts and Crafts, Jungendstijl, and Deco. Artists, architects, and designers collected these Japanese design papers, applying the patterns and strategies in their work. Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, William Morris, and Louis Comfort Tiffany were just a few. Arts and Crafts became Bauhaus, and Bauhaus morphed into Deco. When the last filigree was stripped down to a Mondrian, the style was done.

The Making of a Collection

Knowing this, or maybe not knowing this, my father saw piece by piece, pile by pile of these collections land at auction, galleries and markets in London, Paris, and New York. He had an interesting eye. Sometimes it only took one example to see a whole system. He bought what was available, he sought out the rest. He ended up with an encyclopedic collection.

In the 1890s the Japanese stopped sending stencils to Europe, saying they had run out. They hadn’t. But it is safe to say that the more than 2000 pieces my father acquired are those that informed the West. Enthralled as he was, he organized dedicated exhibits in museums across the U.S., starting with the Asia Society in New York, then moving to Museum of the Art Institute of Chicago (May 1958) and institutions west.

Could you do something with the stencils?

I was sitting under the kitchen table minding my own business when he died. Itwas 1968. The stencils found their way home from various exhibition and were placed gently in crates. They remained there for 50 years. In 2000 my mother asked me–the child with an undergraduate degree in Art History, “Could you do something with the stencils?”

I was not qualified. Maybe no one is but I was the the family member most likely to, with my BA in art history. I didn’t want to hand the collection off to someone else. That choice was more terrifying than my lack of expertise.

“I can try.”

Twenty-one crates landed on my doorstep. What is the best practice for managing masterpieces of a little-known discipline? I opened a crate. Then, I had an epic allergy attack. For the next two weeks I exclaimed “wow” over and over again. Still, I needed someone who knew more than “Wow.”

I called Susanna Campbell Kuo. In 1998 the Santa Barbara Museum of Art held an exhibit of katagami. With it, they produced a fantastic catalog. Carved Paper remains the go-to text on katagami, even though it’s been out of print since it was published. Ms. Kuo is one of the authors. I did a little search. I found her in Lake Oswego and called. She said the nicest thing:

“We’ve been looking for you.”

Ms. Kuo was the first person of expertise to acknowledge the importance of the collection. I bought her a ticket and invited her to my basement. For the better part of a week we went through the collection sheet by sheet. She was able to identify iconography and techniques as well as pointing out the great pieces.

Shortly thereafter, Carolyn Staley Fine Japanese Prints in Seattle represented a small portion of the collection in exhibitions and sales. This was stopped by the recession of 2008. That respite forced me to face the problem of great collections: if you sell off bits, it stops being a great collection. Cumulative knowledge is lost.

What to do? I waited out the recession. I watched. I got to know the collection. I spent twenty years with these objects. Then digital photography evolved, which offered a way to both send the collection out in the world and keep the knowledge and design archive that it held, whole.

The Katagami Project

Every artifact is now documented with a high-resolution digital image, back-lit for clarity and shot with a Hasselblad Phase One, thanks to photographer Johnny Galvan. This format makes artifacts available in the form of usable patterns for architects, designers and artists.

Developer Galen Strasen built a searchable database, making each stencil or pattern accessible based on meaningful and poetic criteria. In this way, the aesthetic resource of the collection can remain intact and accessible as the artifacts are deaccessioned.

The Katagami Project stewards this collection and promotes the appreciation of katagami through shared knowledge in the Katagami Network, in which experts and interested parties can share knowledge and resources. The Katagami Project also hosts events-like Collecting Katagami, and on-line symposium with private and institutional collectors sharing insights and scholarship on their holdings. Collecting Katagami October 20-31, 2023

The katagami in the collection are available for exhibition, loan, scholarship, and use.

Because the world is full of the marvelous things that people make to share.

Happy hunting.

Katina Huston